Last Sunday – a week before Remembrance Day – I led a Peace Walk in Bognor Regis. There were about 15 of us from a mix of churches in Bognor: Catholic, Baptist, United Reform, Pentecostal, Methodist and Quakers. The walk was billed as a mix of poems, questions and a little local history. We experienced what drew our hearts and reflected on what the word ‘peace’ meant to us. We thought about those suffering from war and conflict and symbolically carried them as we walked. But the central part – literally and metaphorically – was at Bognor Town Hall.

Hidden history in the Bognor Regis coat of arms

Just above the entrance to the Town Hall is the Bognor Regis coat of armswhich was largely inspired by the then Vice Chairman of the Town Council, Commander Charles Edward Hudson, OBE, in 1935. Cdr Hudson was a respectable man in many ways. He had served as an officer in the Royal Navy and had a senior job in Dunlop rubber. He was a founder member of the British Legion and a local councillor. He had also joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, set up following a speech by Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) that called for a closer understanding of Germany in order to safeguard peace in Europe. He lived in Limmer Lane, Felpham. The minutes of the council meeting recorded “a hearty vote of thanks be accorded to Councillor Commander Hudson for his valuable assistance” in bringing about the new coat of arms.

I pointed out some of the features of the coat of arms. The gull’s wings show Bognor’s association with the sea; the crown between the wings commemorates the stay of George V at Aldwick; the three martlets (mythical heraldic birds) stand for the old kingdom of Sussex; the oblong gold panel (with martlets) represents the sea wall, built in 1870. The blue and gold of the shield stands for the sea and the sands.

Perhaps the most interesting part is the motto on the crest. This originally read ‘Action’: the title of a Blackshirt (British Union of Fascists) newspaper. The motto ‘Action’ was chosen by Commander Hudson who, in addition to his other activities, was also a prominent member of Sir Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts. The paper contained phrases surprisingly familiar to the present day such as ‘Britain First’ and ‘Britain for the British’ as well as complaints about the impartiality of the BBC in not allowing sufficient airtime to Mosley and condemnation of Jews.

Oswald Mosley and the Fascists on the South Coast

Hudson invited many guests to speak in Bognor and the surrounding area, including Oswald Mosley himself and William Joyce, later known as Lord Haw-Haw, who broadcast Nazi propaganda from Germany to Britain during the war.

Hudson’s daughter later commented that her sister (when aged ten) brother (nine) and she herself (seven) – would join in the excitement when Oswald Mosley came to dinner: painting slogans on street walls, raising their arms in Nazi salute, shouting ‘PJ’ (perish the Jews), and singing an Italian Fascist song.

Mosley spoke at Worthing October 9, 1934. Michael Payne, a local historian, described the scene: ‘Finally the curtain rose to reveal Sir Oswald himself standing alone on the stage. Clad entirely in black, the great silver belt buckle gleaming, the right arm raised in the Fascist salute, he was spell-bindingly illuminated in the hushed, almost reverential atmosphere by the glare of spotlights from right, left and centre. A forest of black-sleeved arms immediately shot up to hail him.’

Mosley spoke at Worthing October 9, 1934. Michael Payne, a local historian, described the scene: ‘Finally the curtain rose to reveal Sir Oswald himself standing alone on the stage. Clad entirely in black, the great silver belt buckle gleaming, the right arm raised in the Fascist salute, he was spell-bindingly illuminated in the hushed, almost reverential atmosphere by the glare of spotlights from right, left and centre. A forest of black-sleeved arms immediately shot up to hail him.’

‘The meeting was disrupted when a few hecklers were ejected by hefty East End bouncers. Mosley, however, continued his speech undaunted, telling his audience that Britain’s enemies would have to be deported: “We were assaulted by the vilest mob you ever saw in the streets of London – little East End Jews, straight from Poland. Are you really going to blame us for throwing them out?”‘

‘At the close of proceedings Mosley and Joyce [presumably with Hudson as well] marched along the Worthing Esplanade, accompanied by a large body of blackshirts. They were protected by all 19 available members of the borough’s police force. A crowd of protesters, estimated as around 2,000 people, attempted to block their path. A 96-year-old woman, Doreen Hodgkins, was struck on the head by a Blackshirt before being escorted away. When the Blackshirts retreated inside, the crowd began to chant: “Poor old Mosley’s got the wind up!”

Cdr. Hudson was interned by the British Government at the start of the war and the town’s motto was an embarrassment. In 1940 the motto was removed from the crest and replaced with the words ‘To excel’.

A secret police report on Fascism in Sussex claimed that “Cdr Hudson… was the leading Blackshirt in West Sussex, and that the number of Blackshirts in Bognor was about 300 – compared to just 60 in Worthing. Mosley decided that the South Coast was an ideal place to hold summer camps. They were held in Pagham, Selsey and West Wittering from 1934 to 1937 to highlight the party’s beliefs and spread them throughout Britain. People from all over the country paid a modest amount for these summer holiday camps and if you weren’t a fascist beforehand, you were expected to be by the end.

Questions for today – and the Kingdom of God

What, I asked those on the Peace Walk, with the benefit of hindsight, what would we wish to have done had we been around in 1935?

What do we think might have made a difference to us had we been heavily under the influence of fascism from our families, schools, places of work, media or society as a whole (as surely, most of us would have been if we had been living in Germany at that time)?

What are the parallels – and the differences – between the situation now and then? Who is continuing the work of the 2,000 people who protested against Mosley in what is happening today – for example in relation to the protests against refugees and asylum seekers in Chichester Park Hotel?

A final question is to consider: what are the implications for the churches in Bognor today, both individually and together. I have no set answer, except to consider and pray for our response.

Peace and the Kingdom of God

‘Blessed are the peace makers’ said Jesus ‘for theirs is the Kingdom of God’. Jesus was not afraid of putting his head above the parapet and engaging with people – especially those he disagreed with. It’s easy to think of peace-making as simply being passive, keeping our heads down in a cosy cocoon while conflict whirls around us. Peace makers do not shy away from conflict but engage with it in a positive, non-violent way. In so doing there may be a sense of vulnerability, moving from the centre to the margins, but in that place discovering a deeper sense of peace which may be called the Kingdom of God.

Next steps:

To help asylum seekers and others in Chichester and Bognor contact https://sanctuaryinchichester.org/

To be a presence to local people, politicians, the media and the asylum seekers themselves against the hate of the far right, join ‘Chichester Welcomes Refugees’ at https://www.facebook.com/groups/3622143458065299

Sources:

On The Bognor Town Crest: https://www.facebook.com/bognorregistc/photos/history-of-the-town-council-crest-bognor-had-been-using-a-coat-of-arms-since-the/2253493521572971/

On Hudson: https://spartacus-educational.com/U3Ahistory46.htm

On Mosley and the Fascists:

https://westsussexrecordofficeblog.com/2019/09/20/documenting-fascism-in-1930s-west-sussex/

Michael Payne: Storm Tide: Worthing: Prelude to War 1933-1939; Publisher: Verite CM

Comment:

| Jeffrey Wallder oswaldmosley.com |

Blessed are the peacemakers indeed! And whilst you led 15 people on your peace march, Mosley led 100,000 people on his peace march through London in May 1940 and in July 1939 his Earls Court Peace Rally was attended by 30,000 people making it the largest indoor meeting in the history of the world. Mosley opposed the Second World War with slogans such as ‘The war on Want is the war we Want’ and ‘Peace with Honour, Empire intact and British people safe.’ This resulted in Mosley and Hudson and over 1,100 of his Blackshirts being imprisoned for years in 1940 without charge, trial or right of judicial appeal. As a result 60-million people died in WW2. Is any war worth 60-million deaths? Mosley said ‘let the Germans push east and engage in a war with the Russians. Whoever won would be so weakened by the ordeal they would be no threat to anybody for a generation – meanwhile Great Britain should build up its army, navy and air force to a size that it need fear no other nation in the world.’ Perhaps you think Mosley wanted Hitler to win WW2? In private he despised Hitler. Once war was inevitable Mosley ordered his Blackshirts to defend this country against the Nazis to the death. And so they did, dying in their hundreds. Did you know the first 2 official casualties of WW2 who died on active service on the second day of war were volunteer RAF aircraftsmen George Brocking and Ken Day, both Mosley Blackshirts, who died whilst attacking the German fleet? Oswald Mosley had guts, he had brains and an infinite capacity to charm. The world will not see his like again for many a long year! |

Lloyd takes as his starting point the etymology of the word sacred, which comes from the Latin sacer, meaning both sacred and accursed: a paradox.

Lloyd takes as his starting point the etymology of the word sacred, which comes from the Latin sacer, meaning both sacred and accursed: a paradox.

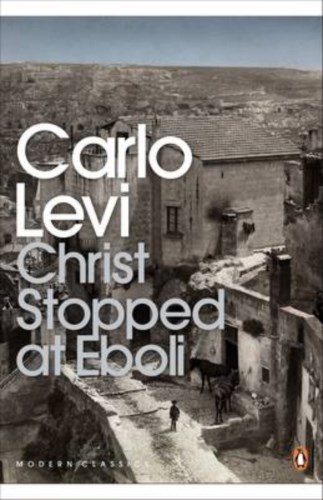

I found this a beautiful book which speaks deeply of the margins. Because of his opposition to Fascism, Carlo Levi was banished at the start of the Abyssinian War in 1935 to a small village, Gagliano, in a remote province of southern Italy.

I found this a beautiful book which speaks deeply of the margins. Because of his opposition to Fascism, Carlo Levi was banished at the start of the Abyssinian War in 1935 to a small village, Gagliano, in a remote province of southern Italy. Picture from abandoned house

Picture from abandoned house

nothing of the struggles which is what, ultimately, make us more human.

nothing of the struggles which is what, ultimately, make us more human.